This repository contains notes from Basic Aspects of Programming with Solidity course from Distributed Lab.

- Ethereum the world computer

- Ethereum transactions and blocks

- Practical cryptography in Ethereum

- Ethereum smart contracts

- Solidity Variables

- Solidity Functions

- OOP in Solidity

- Advanced Solidity: Assembly and data locations

- Proxy and libraries

- Advanced Solidity: Precompiles, signatures, and bytecode

- Token standards, ERC20 tokens

- ERC721 and ERC1155 tokens

-

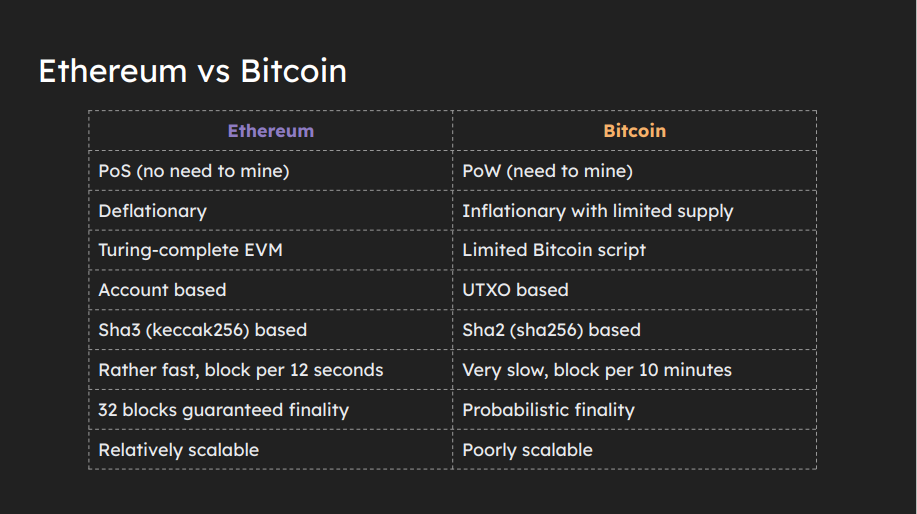

Ethereum is a POS(Proof of Stake) blockchain with 500K+ validators. 1 million transactions happens daily on ethereum and during bull run events it is upto 10 million. It has community of thousands of researchers and developers.

-

Ethereum has EVM which is turing complete. Turing completeness means a system or language can perform any computation, simulate other systems, and has loops, conditionals, unbounded memory, and arbitrary precision.

-

Solidity and Vyper are popular high-level programming languages specifically designed for Ethereum smart contract development. In contrast, the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) operates at a lower level and directly executes low-level instructions called opcodes.

-

Ethereum's ecosystem encompasses a diverse range of on-chain and off-chain components, for example: The Graph which provides a robust infrastructure for decentralized innovation and data indexing on the Ethereum network.

-

In the Ethereum network, every node maintains a complete copy of the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), enabling independent verification and execution of transactions and smart contracts.

-

Within the Ethereum network, the state encompasses Ethereum balances, the state of smart contracts, transaction receipts, and logs that smart contracts emit, forming a comprehensive record of the network's financial and computational activities.

-

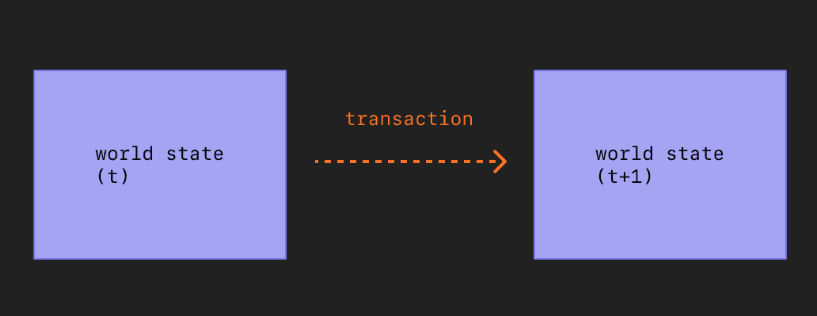

During a transaction in Ethereum, the state of the system undergoes changes, but it may not immediately reach its final state due to the asynchronous nature of the network and the need for consensus among nodes.

-

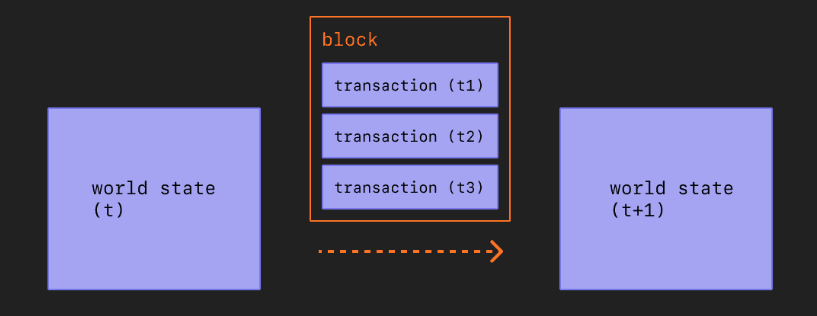

The number of transactions a block can hold in Ethereum depends on the gas limits, with an average throughput of 15-20 transactions per second.

-

Ether serves as the native currency of the Ethereum blockchain, while transaction gas acts as a unit representing the computational complexity of transactions. Ethereum features externally owned accounts for individuals and smart contracts, which are programmable entities that can execute arbitrary on-chain programs.

-

The maximum gas limit for a block in Ethereum is set at 30 million gas, while the cheapest transaction, such as transferring ethers, costs 21,000 gas.

-

The transaction cycle in Ethereum involves sending a transaction, deducting the gas limit from your account, and upon execution completion, receiving a gas refund that returns any unused gas back to you.

-

Gas price in Ethereum is determined by a specialized algorithm introduced in the London hardfork, which incorporates the base fee of the block and an optional tip provided by the sender as compensation for the validator.

-

When the Ethereum network observes that the blocks are consistently exceeding the 15 million gas threshold, the base fee for transactions will increase as a mechanism to manage network congestion and prioritize transaction processing.

-

In Ethereum, each epoch consists of 32 slots, and once an epoch is executed and completed, a new epoch begins, ensuring the finality of blocks and maintaining the progress of the blockchain.

-

When 2/3 or more of the validators in Ethereum accept the validity of an epoch, it achieves a state of safety. Once a new epoch is added on top of the existing one, the epoch becomes finalized, providing assurance and permanence to the blockchain.

- A transaction is an atomic action inititated by EOA that either changes the ethereum state or reverts.

- Regular transactions that send ETH from one account to another (cheapest transaction).

- Contract deployment transactions where 'to'is address(0) and data is contract creation bytecode.

- Transaction that interact with an already deployed smart contract where 'to' is address of the smart contract and execution payload is in data field.

- Nonce: Special counter that ethereum maintains, to keep count of EOA transactions initiated.

- Max priority fee per gas: Max price of a validator tip per consumed gas (London hardfork).

- Max fee per gas: Base Fee + Priority Fee

- Gas Limit: max amount of gas the transaction can consume.

- Recipient: destination ethereum address.

- Value: amount if ETH(wei) sent to the recipient.

- Data: When interacting with the smart contract, it is ABI encoded execuion payload. When deploying a contract data is bytecode of the contract.

- v,r,s : ECDSA signature of the EOA.

- EIP 2718 introduced a "transaction envelope" to support future transaction types (users to specify which type of transaction they are sending).

- chain id is included in the RLP encoding to mitigate transaction replays on the other EVM chains (chain id for ethereum mainnet is 1).

- Transaction hash is a keccak256 hash of its signed RLP counterpart.

- Transaction is constructed, signed, and RLP encoded.

- Transaction hash is calculated.

- Transaction is broadcast to the network and added to the mempool.

- Validator picks a transaction from the mempool and includes it in a block.

- Block gets added to the chain and the transaction executes.

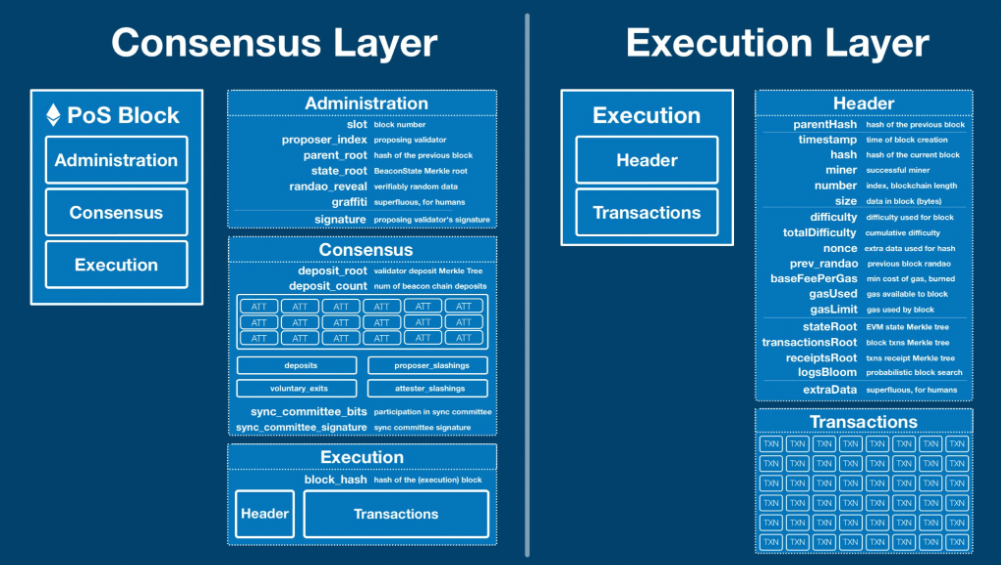

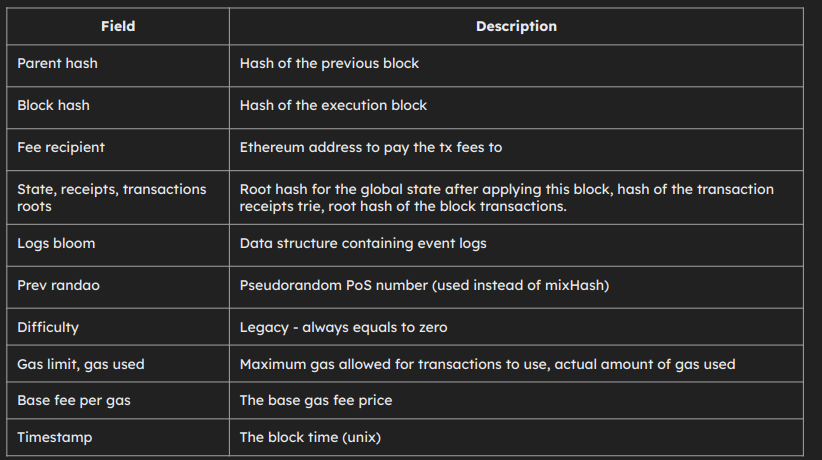

- The Ethereum block is a complex structure that contains both the intricate PoS consensus information and the transactions execution payload.

- Execution payload is contained within the new PoS consensus.

- The list of transactions.

- Block validator is pseudorandomly but deterministically chosen via PoS consensus algorithm.

- Validator assembles the block as he wishes to maximize profit (MEV).

- Validator executes block transactions one by one and sends the block to peers.

- At the end of the epoch attestation on block validity begins.

- Block gets marked as safe.

- After another epoch block gets marked as finalized.

- Cryptography is the branch of mathematics that ensures the confidentiality and authenticity of information.

- Cryptography lies in Ethereum roots and makes up a descent part of its operability. Ethereum highly utilizes hash functions, public key cryptography, and digital signatures. Cryptography is used to control Ethereum users’ funds, process transactions, maintain Ethereum state, etc.

- A hash function is a function of converting an array of input data of arbitrary length into an output bit string of fixed length, which is performed using a certain algorithm.

- Keccak256 (sha-3 family), used pretty much everywhere in the platform. From the construction of addresses and tx hashes, to the hash function of Merkle-patricia state tree.

- Sha256 (sha-2 family), available as a precompile at address(2).

- Ripemd160, available as a precompile at address(3).

- A cryptographic key is a digital sequence of a certain length, created according to certain rules, using random (or pseudo random) number generators and / or calculated according to a special algorithm from other values.

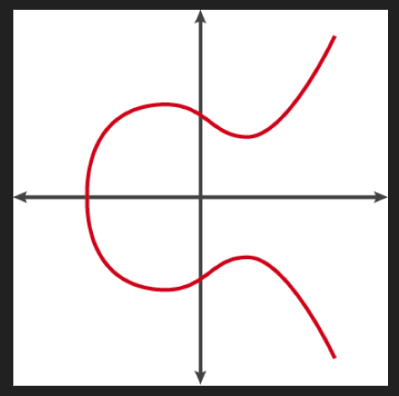

- Ethereum uses elliptic curve public key cryptography.

- The secp256k1 elliptic curve is used.

- The EOA private key is a unique account identifier.

- Smart contracts do not have private keys.

- A seedphrase is an entropy to the private keys generator.

- Generate a private key k.

- Multiply k by the elliptic curve generator point G to get the public key K.

- Concatenate x and y coordinates of K.

- Calculate H the keccak256 hash of the concatenation.

- Take 20 the least significant bytes of H. This will be an EOA address.

- The address may be “hidden” behind an ENS name.

- A digital signature is an analogue of a handwritten signature that provides two properties: the ability to verify the authenticity and integrity of the document, which protects it from modification and substitution.

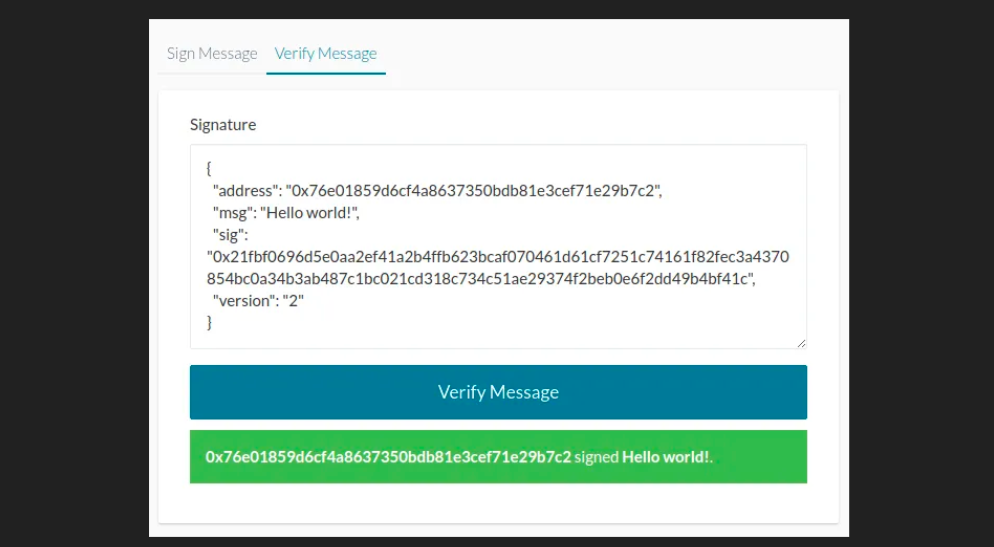

- Ethereum uses the RFC-6979 standard of ECDSA to make signatures deterministic without security compromises. The determinism is achieved by providing the keccak256 hash of the concatenation of the private key with the message as an entropy to ECDSA.

- ECDSA outputs 3 parameters: V, R, S. Where R and S are the parts of the signature and V is a recover identifier (27 or 28).

- EcRecover precompile is available at address(1).

- The vanila ECDSA, where message hash gets signed, used for signing transactions.

- The personal sign, where to the original message the prefix “\x19Ethereum Signed Message:\n” + len(message) is added.

- The typed sign, where the typed message is elaborately constructed to mitigate the signature replays.

- When EOA constructs the transaction there is no “from” field.

- The EOA signs the transaction via their private key using ECDSA.

- When transaction is sent, the VRS parameters together with raw transaction bytes are broadcast to the nodes.

- Courtesy of ECDSA, the nodes recover the EOA address from VRS and raw transaction bytes.

- Ether from the recovered EOA is deducted to pay for gas.

- Implementing secure signature verification in Solidity is hard. There are many attack vectors to consider.

- Rule of thumb is if signatures are involved, they should cover the most parameters.

- User signatures must be EIP-712 compliant.

- Never use ecrecover precompile directly.

- In Ethereum terms, smart contracts are immutable decentralized programs that run deterministically in the context of EVM. They are neither smart nor legal contracts, but the term has stuck.

- Smart contracts are usually written in a high-level language like Solidity or Vyper and then compiled to bytecode.

- Smart contracts are used to bring real world concepts and value to Ethereum.

- Smart contract is designed, implemented and compiled to bytecode.

- Smart contract is extensively tested and audited.

- Smart contract is deployed via a special transaction and its address is determined.

- Users atomically interact with a smart contract either directly or through DAPPs. The contract may in turn interact with other contracts.

- Smart contract may be destructed if it allows so. Deprecated feature.

- Solidity is a contract oriented programming language created by Gavin Wood. The main product is a compiler, solc, which converts programs to the EVM bytecode. The latest version is 0.8.19.

contract Example {

event RecievedEther(uint256 amount);

address public owner;

constructor() {

owner = msg.sender;

}

recieve() external payable {

emit RecievedEther(msg.value);

}

function withdrawEther() external {

require(msg.sender == owner, "Not an owner");

(bool ok,) = msg.sender.call{value: address(this).balance}{""};

require(ok, "Failed to send ether");

}

}- Dapps interact with smart contracts through function calls and event listening. They invoke functions defined in the contract using the ABI, which specifies function names, parameters, and return types. dApps can also retrieve contract data and respond to events emitted by the contract. This interaction enables dApps to execute functions, access contract state, and provide real-time updates based on contract events.

- Value types in solidity are used inside the functions and mostly lives on stack.

bool (aka uint8)

int8, int16, …, int256 (signed integers, 0xff..ff = -1)

uint8, uint16, …, uint256 (unsigned integers, 0x00..01 = 1)

address, address payable

bytes1, bytes2, …, bytes32 (0x10..00 = 1)contract Example {

function foo() external {

bytes4 selector = Example. foo. selector;

address caller = msg. sender;

uint256 callerUint256 = uint256(uint160 (caller));

bool areEqual = ~(int256(0)) == int256(-1);

}

}- Special types of variables that consume more memory than stack allows, so they are placed on memory(heap).

- bytes (tightly packed raw bytes)

- string (tightly packed UTF-8 encoded characters)

- Fixed length arrays

- Dynamic length arrays

contract Example {

function foo() external {

bytes memory someBytes = hex"112233445566";

string memory someString = "Hello, world!";

uint256[1 memory numbers = new uint256[1(10)];

address [2] memory addresses = [address(1), address (2)];

// Dynamic array of static arrays of strings

string(2][] memory complexArray = new string[2][](5);

}

}- lives mostly in memory with stack pointers, made by aggregation of several other value types or memory types.

contract Example {

struct User {

string name;

address account;

uint32 age;

}

function fool() external {

User memory user = User({name: "Bob", account: msg .sender, age: 223});

}

} - In Solidity, type aliases allow developers to define alternative names for existing types, making code more readable and providing a way to create custom types based on existing ones.

type MyUint is uint256;

library MyUinter {

function add(MyUint a, MyUint b) internal pure returns (MyUint) {

return MyUint.wrap(MyUint.unwrap(a) + MyUint. unwrap(b));

}

}

} - Right now Solidity doesn’t support fixed point numbers, so to overcome the limitation simple trick is used.

- The on-chain calculations are made on uint256 numbers with increased precision. When the result is needed, off-chain services query the contract and decrease the precision back.

- So 2 / 100 would be 2 * / 100.

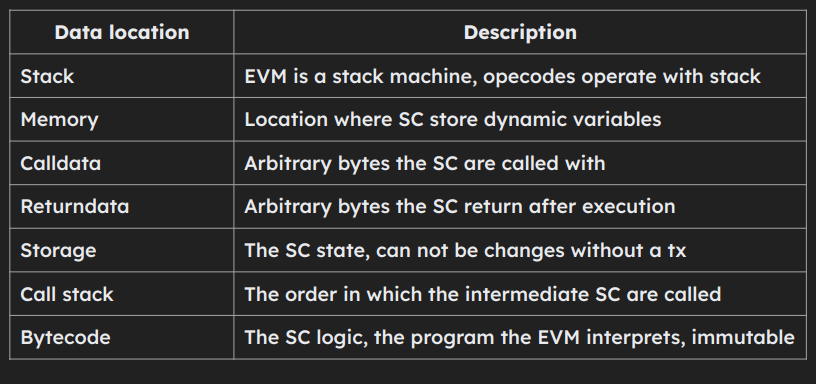

- Local variables (stack)

- Memory

- Calldata and returndata

- Storage

- Constants and immutables

- Stack location refers to the memory location where variables and function parameters are stored during contract execution. It is a temporary storage area used for efficient processing and typically used for variables with a limited scope within a function.

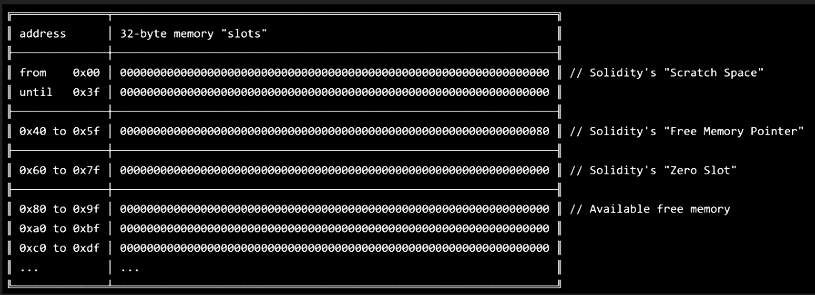

- Memory is a data location where smart contracts store temporary data. Memory is zeroed at the start and destroyed at the end of the call context. Maximal accessible memory pointer is 2**256-1.

-

calldata: It is an immutable and read-only area of memory that contains the function arguments and data sent from an external contract or externally owned account (EOA) when calling a function. Solidity functions can access and read data from calldata but cannot modify its contents. -

returndata: It is the memory area used to store the return values and data sent back by external function calls. When a contract invokes a function on another contract, the return data from that function call is stored in returndata. The calling contract can read and process the returned data.

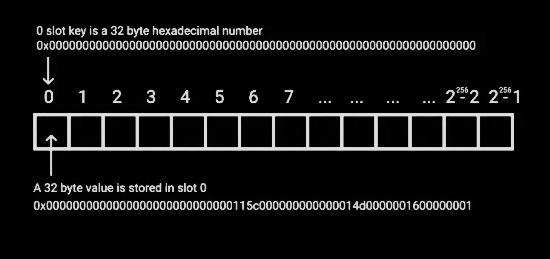

- Storage is a data location where smart contracts store their state. Storage is a map of 32-byte slots to 32-byte values. If anything is written to storage, it is retained past the completion of the transaction. Non-initialized slots return zero when read.

- Constants and immutables are special types of variables that live in the contract’s bytecode. - Constants are (usually) evaluated during compilation and immutables during contract’s deployment. After that they are encoded directly in the bytecode where they are used.

contract Example {

address internal constant ADMIN = address (5);

address internal immutable SELF;

// storage slot 0 for length

// slot keccak256(0) for data if length is > 31 bytes

string public name;

constructor () {

SELF = address(this );

}

function setName (string calldata name_) external {

require(msg.sender == ADMIN, "Not and admin");

name = name:

}

} - Solidity functions are like open endpoints of smart contracts. Anyone can call and use them. It is fully a smart contract’s responsibility to add proper access control checks and guarantees that the execution is safe for the end user.

contract Example {

function foo(uint256 var) external view returns (address user);

} signature: "foo(uint256)" (name of the function and type it accepts).selector: keccak256("foo(uint256)")[:4] = 0x2fbrbd38 (first 4 bytes of keccak256 hash).- function selector is a special value that solidity uses to distinguish which function you are calling from the outside, to enter the exact function you're calling.

- Functions can be

external,public,internal, andprivate. - Variables can be

public,internal,private, anddefault.

contract Example {

uint256 public counter;

function increment() external returns (uint256) {

return ++counter;

}

} - Functions can have built-in and custom modifiers applied. Built-in modifiers are:

view,pure,payable,override, andvirtual.

contract Example {

address public owner;

modifier onlyOwner() {

require(owner == msg.sender, "Not an owner");

_;

}

constructor () {

owner = msg. sender;

}

function changeOwner (address newOwner) external onlyOwner {

owner = newOwner;

}

} -

Opcode create. Address is calculated as

keccak256(RLP([<sender>, <nonce>]))[12:]. Smart contracts also have nonces, but they start from 1. -

Opcode create2. Address is calculated as

keccak256(0xff, senderAddress, salt, keccak256(init_code))[12:]

contract Example {

function deploy() external {

A a = new A() ;

B b = new B{salt: bytes32(1)}();

}

} interface Callee {

function foo(uint256 amount) external;

}

contract Example {

function testCall(address callee) external {

// high-level call

Callee(callee). foo(1);

// low-level call

(bool ok,) callee.call(abi.encodewithSignature("foo(uint256)", 1));

// delegatecall

(ok,) callee.delegatecall(abt.encodeWithSelector(Callee.foo.selector, 1));

// staticcall

(ok,) = callee.staticcall(abt.encodewithSelector(Callee.foo.selector, 1));

// callcode DEPRECATED

(ok,) callee.callcode(abi.encodewithSelector(Callee.foo,selector, 111;

}

}contract Example {

function bar() public;

function foo() external {

this.bar(); // creates a subcontext = call

bar(); // jump

}

} this.bar()creates a subcontext call, msg.sender insidebar()function will be address of example contractbar()msg.sender will be externally owned account

- Solidity distinguishes static and dynamic types. Static types are encoded in-place (head) and dynamic types are encoded with a calldata offset (head + tail).

abi.encodeWithSignature("deposit(address,uint256)", msg. sender, le18);

->

0x47e7ef24

0000000000000000000000005b38da6a701c568545dcfcb03fcb875f56beddc4

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000de0b6b3a7640000- static types: (

uint256,uint128,bytes32, encoded in place -> directly translated into some bytes). - dynamic types: dynamic array, struct with dynamic arrays,

bytes,strings. encoding of head & tail.

- Solidity events are an abstraction on top of the EVM’s logging functionality. Applications can subscribe and listen to these events through the RPC interface of an Ethereum client.

contract Example {

event ReceivedEther(uint256 amount);

receive() external payable {

emit ReceivedEther(msg.value);

}

} - Events have special “topics” that applications can filter events by.

- 3 topics maximum for normal and 4 for anonymous events.

- 0st topic for non-anonymous event is an event signature.

contract Example {

event ReceivedEther(uint256 indexed amount);

event ReceivedEtherAnon(uint256 amount) anonymous;

receive() external payable {

emit ReceivedEther(msg.value);

emit ReceivedEtherAnon(msg.value);

}

} - There are 3 types of error handling functions: require, revert, assert. Throw is deprecated. Assert used to consume all the provided gas, but Solidity 0.8.0 changed that.

contract Example {

error NotWhitelisted(address token);

function deposit(address token, uint256 amount) external {

assert (amount > 0);

if (!whitelisted[token]) {

revert Notwhitelisted(token) ;

}

require(IERC20(token).transferfrom(msg.sender, address(this), amount), "Transfer failed");

}

} contract Example {

error CustomError();

function doRevert() external {

revert("Oops");

}

function foo() external {

try this.doRevert() {

...

} catch Error(string memory reason) { // "Oops" will be here

...

} catch Panic(uint256 code) {

...

} catch (bytes memory reason) { // CustomError will be here

...

} catch {// equivalent to catch (bytes memory reason)`

}

}

} contract Example {

mapping(address => uint256) public deposits;

function deposit() external payable {

deposits [msg.sender] += msg.value;

}

function withdraw() external {

(bool ok, ) = msg.sender.call({value: deposits[msg.sender]}("");

require(ok, "Transfer failed");

delete deposits [msg.sender];

}

} - Object-oriented programming (OOP) is a programming paradigm based on the concept of "objects", which can contain data and code. The data is in the form of attributes or properties, and the code is in the form of procedures or methods.

-

Classes: the declaration for the data format and available procedures for a given type or class of object. Classes contain the data members and member functions.

-

Objects: instances of classes.

-

The Single-responsibility principle: there should never be more than one reason for a class to change. In other words, every class should have only one responsibility.

-

The Open-closed principle: software entities should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

-

The Liskov substitution principle: functions that use pointers or references to base classes must be able to use objects of derived classes without knowing it.

-

The Interface segregation principle: clients should not be forced to depend upon interfaces that they do not use.

-

The Dependency inversion principle: depend upon abstractions, not concretions.

- There are no classes is Solidity but there are contracts.

- There are no objects as is. Every deployed contract can be thought of as an object.

- What contracts do is they define an ABI encoding/decoding interface to interact with each other.

- There is no object <> class coupling. You can use any contract declaration to represent any deployed contract (as long as the interfaces match).

abstract contract A {

function setA(uint256 a_) external virtual;

}contract A {

uint256 public a;

function setA(uint256 a_) external {

a = a_;

};

}interface IA {

function setA(uint256 a_) external;

}- Abstract contracts are contracts which can not be deployed but just have function declarations.

- Interface can't have: state variables, modifiers declared, extend from contracts, functions with bodies defined.

- Interfaces only define function signature & define what those functions return, virtual by default.(declare structs & events)

import {IERC20} from "@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/IERC20.soL";

import {ERC20} from "@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol";

interface MyERC20 {

function transfer(address to, utnt256 amount) external returns (bool);

function balanceOf(address user) external view returns (uint256);

}

abstract contract MyOtherERC20 {

function transfer(address, uint256) external virtual returns (bool);

function balanceOf(address) external view virtual returns (utnt256);

}

contract A {

address public owner = msg.sender;

function transferToOwner(address token) external {

// equivalent transfers

ERC20(token).transfer(owner, ERC20(token).balanceOf(address(this)));

IERC20(token).transfer(owner, IERC20( token). balanceOf(address(this)));

MyERC20(token).transfer(owner, MyERC20( token). balanceOf(address(this)));

MyOtherERC20(token).transfer(owner, MyOtherERC20( token). balanceOf(address(this)));

}

}- Even though there are no traditional classes, Solidity supports contracts inheritance, function overloading and function overriding.

contract A {

function foo() external virtual returns (address) {

return address(1);

}

function foo(uint256) external returns (address) {

return address(1);

}

}

contract B is A {

function foo() external override returns (address) {

return address(2);

}

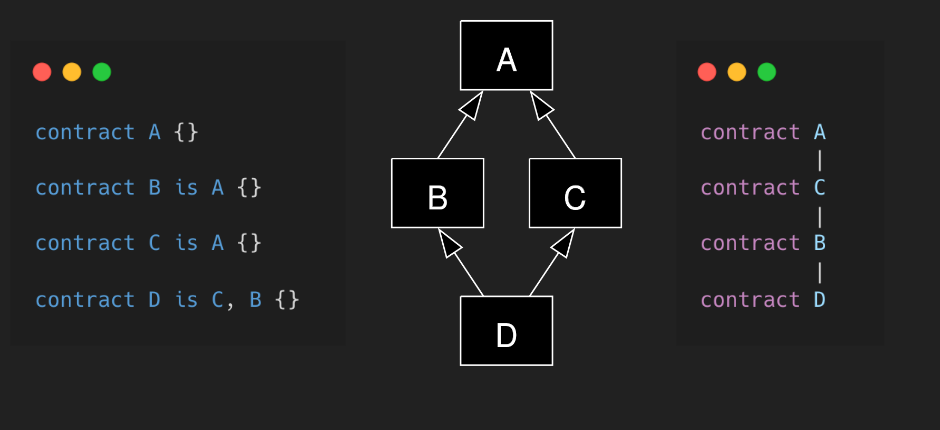

}- Solidity supports multiple inheritance and implements it the same way the Python does. It uses C3 linearization to force a specific order of classes in the directed acyclic graph (DAG) of base classes. In Solidity the order in “is” directive is important: it starts from the most-base and ends with the most-derived class (reversed to Python).

-

The Solidity diamond problem occurs when a smart contract inherits from multiple parent contracts, and some of these parents share a common ancestor with functions or state variables. This creates ambiguity, as Solidity cannot determine which parent's implementation to use.

-

To resolve this, Solidity employs the C3 Linearization algorithm to determine the order in which the parent contracts are linearized, ensuring each function or state variable is inherited only once. Developers must be mindful of this issue when using multiple inheritance in Solidity and carefully design their contract hierarchy to avoid conflicts and unexpected behavior.

-

Legacy compilation: Variables are evaluated in the top-to-bottom inheritance DAG order. Constructors are executed in the top-to-bottom inheritance DAG order.

-

Via IR (intermediate representation) compilation: Variables together with constructors are executed in the top-to-bottom inheritance DAG order.

-

Init code is the contract’s bytecode after its compilation including ABI encoded constructor arguments. This is the same bytecode that is used in the tx “data” field. Init code can’t be more than 48kb.

-

Runtime code is the contract’s bytecode after its constructor execution. Runtime code can’t be more than 24kb.

- Storage layout follows the inheritance DAG order.

contract A {

uint256 public a; //slot 0

}

contract B is A {

uint256 public b; //slot 1

}

contract C is A {

uint256 public c; //slot 1

}

contract D is C, B {

// a -> slot 0

// c -> slot 1

// b -> slot 2

uint256 public d; //slot 3

}- Opcodes are EVM instructions that the smart contract’s bytecode consists of. Opcodes can push/pop elements to/from the stack, access memory and storage, read calldata, and manipulate returndata. Opcodes are also used to call and create other contracts, and emit events.

- Examples: add (0x01), caller (0x33), mload (0x51), sstore (0x55), push32 (0x7f), delegatecall (0xf4), create2 (0xf5).

- Yul is a low-level programming language that can be used to write smart contract on its own or as an “inline assembly” inside Solidity. Yul is directly translated to opcodes and has to used with extreme caution.

- Also the new Solidity codegen (IR compilation) uses Yul as an intermediate representation which is then translated to bytecode. This enables more optimization to take place.

contract Example {

function sum(uint256 a, uint256 b) external pure returns(uint256) {

uint256 res;

assembly {

res: = add(a,b);

}

return res;

}

}object "Example" {

code {

datacopy(0, dataoffset("runtime"), datasize("runtime"))

return(0, datasize("runtime"))

}

object "runtime" {

code {

switch selector()

case 0xcad0899b /* sum(uint256, uint256) */

let a:= calldataload(0x4) //load the first variable in calldata

let b:= calldataload(0x24) //load the second variable in calldata

mstore(0, add(a,b))

return(0, 0x20)

} default {revert(0,0}

function selector() -> s {

s:= shr(224, calldataload(0))

}

}

}- Opcodes manipulate stack. Some opcodes pop elements from it, some push. There are opcodes for arithmetical operations as well.

- Solidity compiler “remembers” where the value of local variables is stored on stack.

- The opcodes are laid in the reverse polish notation (postfix).

- The stack size can’t exceed 1024 elements, otherwise the EVM will revert the transaction.

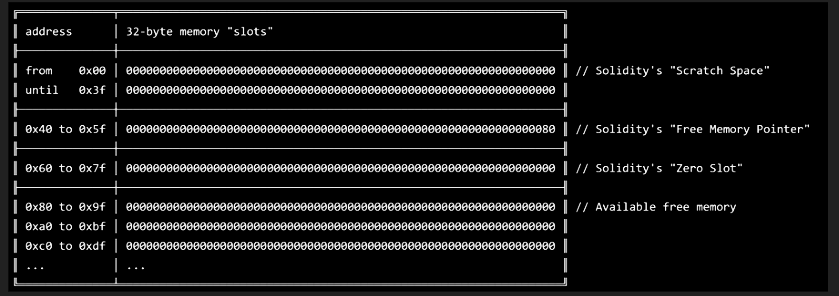

- Memory is a mapping between pointers and slots.

- The maximal value of a pointer is 2**256-1.

- Slots hold 32 byte values. There is no elements packing.

- There is a memory expansion cost (gas) the EVM tracks to limit the actual memory usage. The cost is quadratic to the maximal pointer used (read or write).

- Memory is reset for every new subcontext call. However, you can’t be sure that there is no garbage in the freshly allocated memory.

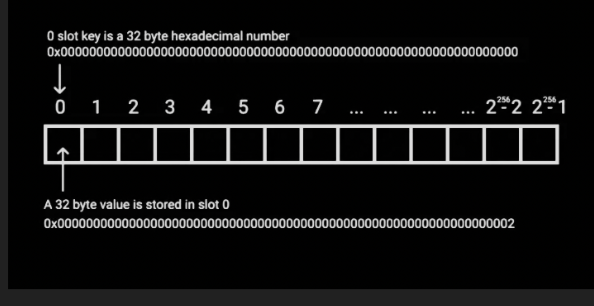

- Storage is a mapping between slot numbers and slot values that are bound to a specific contract.

- The maximal slot number is 2**256-1.

- Slots hold 32 byte values. Elements might be packed.

- Storage is persistent and preserved between transactions.

- Depending on the current slot value, the value that we write right now, and the value before the transaction the cost is estimated.

- The length is stored at slot 0. The values are stored starting from slot keccak256(0).

contract Example {

uint256[] public arr;

function foo() external {

arr[0] = 1;

arr[1] = 2;

}

}- The length is stored at slot 0. The values are stored starting from slot keccak256(0).

- Calldata is a sequential data location very similar to memory.

- Calldata is read only for smart contracts.

- For every zero calldata byte 4 gas is paid. For every non-zero 16 gas.

- When smart contract is called, new calldata subcontext is allocated.

- Usually calldata is ABI encoded. Also it may be a smart contract bytecode in case of deployment transaction.

contract Example {

function foo(bytes calldata someBytes) external pure returns (bytes calldata) {

return someBytes;

}

}-Calldata can be returned from the function. In that case it is just “forwarded” to the returndata.

- Returndata is a sequential data location very similar to memory.

- Returndata can be written by return and revert opcodes.

- Returndata always stores the value of the latest called smart contract.

- Usually returndata is ABI encoded, regardless of the opcode used.

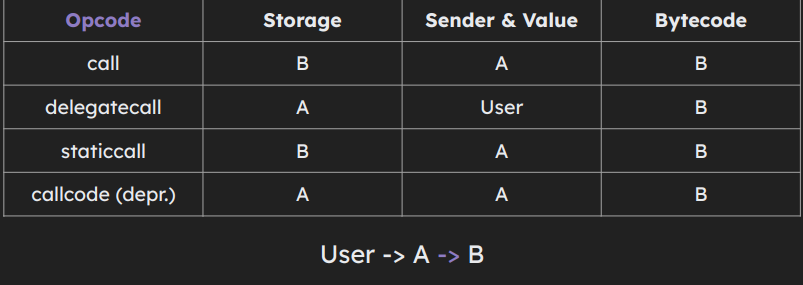

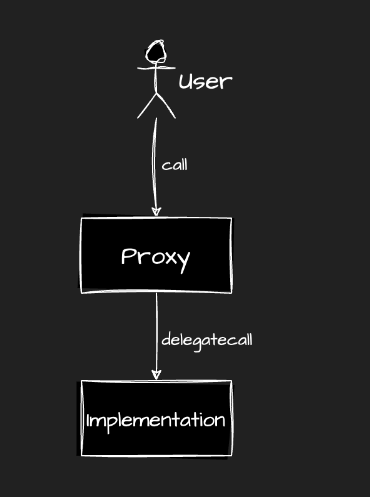

- Proxies are special lightweight smart contracts that are placed on top of regular contracts (implementations) and are needed to provide upgradeability and deployment expenses savings. Proxy contracts work courtesy of delegatecall opcode.

- Proxies are standalone contracts that leverage the concept of a fallback function and a delegatecall.

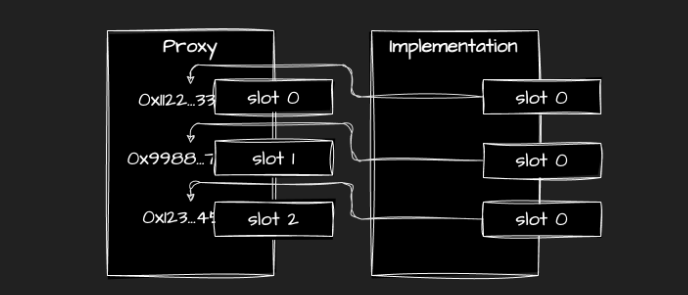

- Proxies keep the implementation address in a special slot to mitigate storage collisions.

- When a user calls a proxy, the call is forwarded to a fallback function. The fallback then delegatecalls the implementation, using the provided calldata.

- The implementation bytecode is executed on the proxy storage.

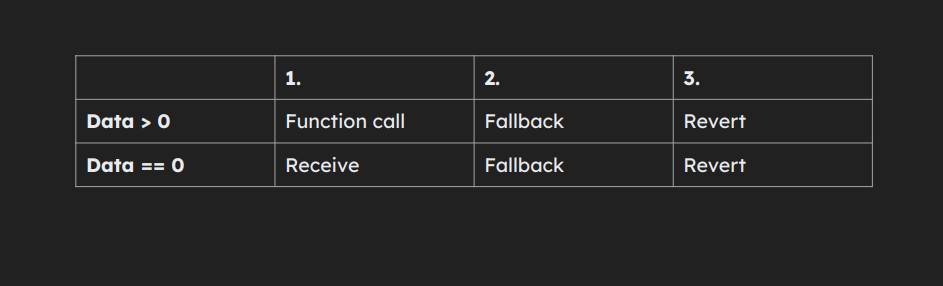

- receive function must be payable, can be virtual.

- fallback function may be payable, can be virtual.

- Storage collision happens when a proxy and an implementation contracts use the same slot N to store their data. Due to the delegatecall, one contract might override the data of another.

- Proxy contracts can upgrade their implementations to overcome the bytecode immutability limitation.

- Proxy contracts are usually small (1 kb) which makes them less expensive to deploy.

- Proxy contracts enable the usage of amazing patterns like Diamond proxy and Contracts Dependencies Registry.

- Because proxies may upgrade their implementations, using them reduces the trust to the protocols.

- Upgrading contracts is not simple due to storage collisions. Usually contract upgrades bring bugs.

- Clients might think that proxies are “a cure for all diseases”. However proxies should only be used for bug fixes & optimization purposes.

- Transparent proxy

- UUPS proxy

- Beacon proxy

- Minimal proxy (clones)

- Diamond proxy

- Inherited storage proxy

- Libraries are contracts that can’t have storage, constructors, fallback, receive functions and can’t be inherited from. Solidity has 2 types of libraries: internal and external. Internal are inlined and called via jumps while external are called via delegatecalls and have to be specifically linked to the callees.

- “Using” keyword is a solidity syntax sugar to indicate that certain variable has to be passed first to a library function.

- Internal libraries are stateless contracts that can’t be deployed on their own. They can only have internal and private functions. Internal libraries are inlined into the “main” contract during compilation.

- External libraries are stateless standalone contracts that have external functions. External libraries are deployable and have to be linked with the “main” contract after compilation. Non-view external functions can only be delegatecalled.

- During compilation Solidity “reserves” certain bytecode where external library is called. “Reservation” is the first 17 bytes of keccak256 hash of a library full name.

- The linker looks for those reserved places and substitutes the placeholder with the actual library address.

- External libraries work with extended ABI encoding. They can work with storage references.

- External libraries are separate contracts, so they help with bytecode splitting.

- External libraries are stateless. They can be deployed once and used by many other contracts.

- Precompiles are special smart contracts that come natively with Ethereum. They are built on top of EVM to extend its functionality. Currently there are 9 precompiled contracts available. All of them live on addresses from (0x01) to (0x09).

- ecrecover (0x01), ECDSA recovery algorithm.

- sha256 (0x02), sha256 hash function implementation.

- ripemd160 (0x03), ripemd160 hash function implementation.

- identity (0x04), returns whatever is input. Used to copy memory.

- modexp (0x05), calculates (B^E) % M with arbitrary precision.

- ecadd (0x06), alt_bn128 elliptic curve addition.

- ecmul (0x07), alt_bn128 elliptic curve multiplication.

- ecpairing (0x08), alt_bn128 elliptic curve pairing.

- blake2f (0x09), compression function used in blake2 hash function.

- Precompiled contract never revert. They either return 0 or nothing if an error occurs.

- EXCODESIZE and similar opcodes treat precompiles as EOAs. Meaning that these opcodes do not detect any bytecode under precompiles.

- Precompiles work with calldata. Even though the accepted format differs from ABI encoding, it is still possible to call precompiles this way.

- The unlock function passes if address(0x02) or address(0x03) are supplied.

- Ethereum users mainly utilize 2 types of digital signatures: ECDSA in the execution client to sign transactions and messages. Also precompile (0x01) is used to recover the signer on-chain.

- EIP-191 and EIP-712 describe how to construct and sign messages.

- BLS in the consensus client to sign slots attestations. BLS is used as those kind of signatures might be easily aggregated for network optimization.

- There are several use cases where message signatures may be used:

- May be used by trusted parties to “approve” some sort of action for users.

- May be used in a multisig.

- May be used to let users sign platform terms and conditions.

- May be used as an entropy to an encryption key generator.

- Replay attacks are possible: cross-chain, cross-contract, cross-function.

- Replay attacks are mitigated.

- Always consider using EIP-712 over EIP-191.

- Never use EIP-191 if it is a message that users have to sign.

- EIP-191 is needed to distinguish between message & transaction signatures.

- Proper EIP-712 makes message signature replay attacks impossible.

- EIP-712 is a bit more expensive and cumbersome to work with.

- Init code is the contract’s bytecode after its compilation including ABI encoded constructor arguments. This is the same bytecode that is used in the tx “data” field. Init code can’t be more than 48kb.

- Runtime code is the contract’s bytecode after its constructor execution. Runtime code can’t be more than 24kb.

List additional resources such as books, tutorials, online courses, or other repositories that could be useful for learning Solidity and Ethereum.

If you would like to contribute to this repository, please follow the guidelines in CONTRIBUTING.md.

This repository is licensed under the MIT License.