Clone this repository by running git clone https://github.com/TreeHacks/hackpack-arduino-app.git from your command line. It includes this README and sample code.

Arduinos are a type of microcontroller that are equipped with a combination of analog equipped with a combination of analog (A1-AX) and digital (1-Y) pins (see graphic below). Analog pins allow the Arduino to sense a voltage within a particular range. When using an analog sensor, this range can be 0-3.3V or 0-5V, depending on how the sensor is wired. Digital pins can be used to sense or output a binary signal - either high (5V on the Arduino Uno), or low (0V on the Arduino Uno). Because they can read and write high or low values, digital pins can be used to transfer data in various communication protocols.

To get started, install the Arduino IDE from here. Follow the instructions on the installer, until you have the IDE downloaded. Then, just plug in your Arduino and you're ready to go! Arduino is programmed in a language that is based off of C/C++, but can also be interfaced in a variety of other languages. While we will not be going over these in this tutorial, links to tutorials for such languages can be found here.

When you first open the Arduino IDE, it will open up starter code that is the basis for all Arduino programs. Let's take a look at this code to understand what it means.

void setup() {

// put your setup code here, to run once:

}

void loop() {

// put your main code here, to run repeatedly:

}All code starts with a setup() and loop(). The setup() code should consist of code that you need run only once - anything to setup the Arduino, or initialize pin modes. When working with Arduino pins, you have to declare what you will be using the pins for: using pinMode(pin_number, pin_mode), where the pin_mode can be either INPUT, OUTPUT, or INPUT_PULLUP.

The loop() code should consist of anything that will be looped - in this runs the main part of your code, with reading sensor values, performing functions, controlling servos and other outputs. One such output is directly controlling a pin's output state, using digitalWrite(pin_number, output_state), where the output_state can be HIGH (1), which sets the pin voltage to 5V (or 3.3V depending on the Arduino) or LOW (0), which sets the pin voltage to 0V or GND. Other important functions include delay(time), allowing you to pause the sketch for time milliseconds.

One of the most basic sketches is as follows. This allows you to turn on and off the on-board LED connected to the Arduino every second.

void setup() {

pinMode(LED_BUILTIN, OUTPUT); //set the pin_mode as OUTPUT

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, LOW); //start off the pin as LOW

}

void loop() {

delay(1000); //wait 1 second

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, HIGH); //set the pin to HIGH (5V)

delay(1000); //wait 1 second

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, LOW); //set the pin to LOW (0V)

}The other pin_mode's - INPUT and INPUT_PULLUP - are explained in the section below.

The pinmodes INPUT and INPUT_PULLUP allow you to gain

access to a myriad of information from the 'outside world.' The analog pins allow you to read an analog value ranging from 0-5V (with a 10 bit precision from 0-1023), and thus can read information from many different sensors. Digital pins allows you to read data with 1 bit precision (0 or 1), and can be used for buttons, switches, and some other types of sensors.

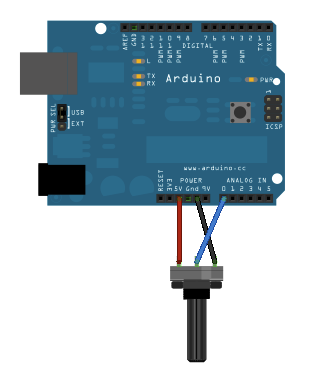

To read an analog input from a potentiometer, the following code and schematic can be used.

void setup() {

// initialize serial communication at 9600 bits per second:

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop() {

int sensorValue = analogRead(A0);

// print out the value you read:

Serial.println(sensorValue);

delay(1); // delay in between reads for stability

}Analog pins do not need to be configured as input pins using pinMode(INPUT), as they are already automatically configured as such

Analog sensors allow the Arduino to sense a voltage that indicates the sensor's current reading; for example, a thermistor is a resistor that changes resistance depending on the current temperature. By building a circuit with a thermistor, the Arduino can determine the current temperature as a function of the sensor's resistance.

Digital sensors can communicate with the Arduino using a variety of protocols, such as I2C or SPI. These protocols allow the sensor to transfer data to the Arduino. In contrast to the thermistor, which required an Arduino to read the sensor's resistance and determine the temperature, a digital temperature sensor may simply transmit the current temperature to the Arduino.

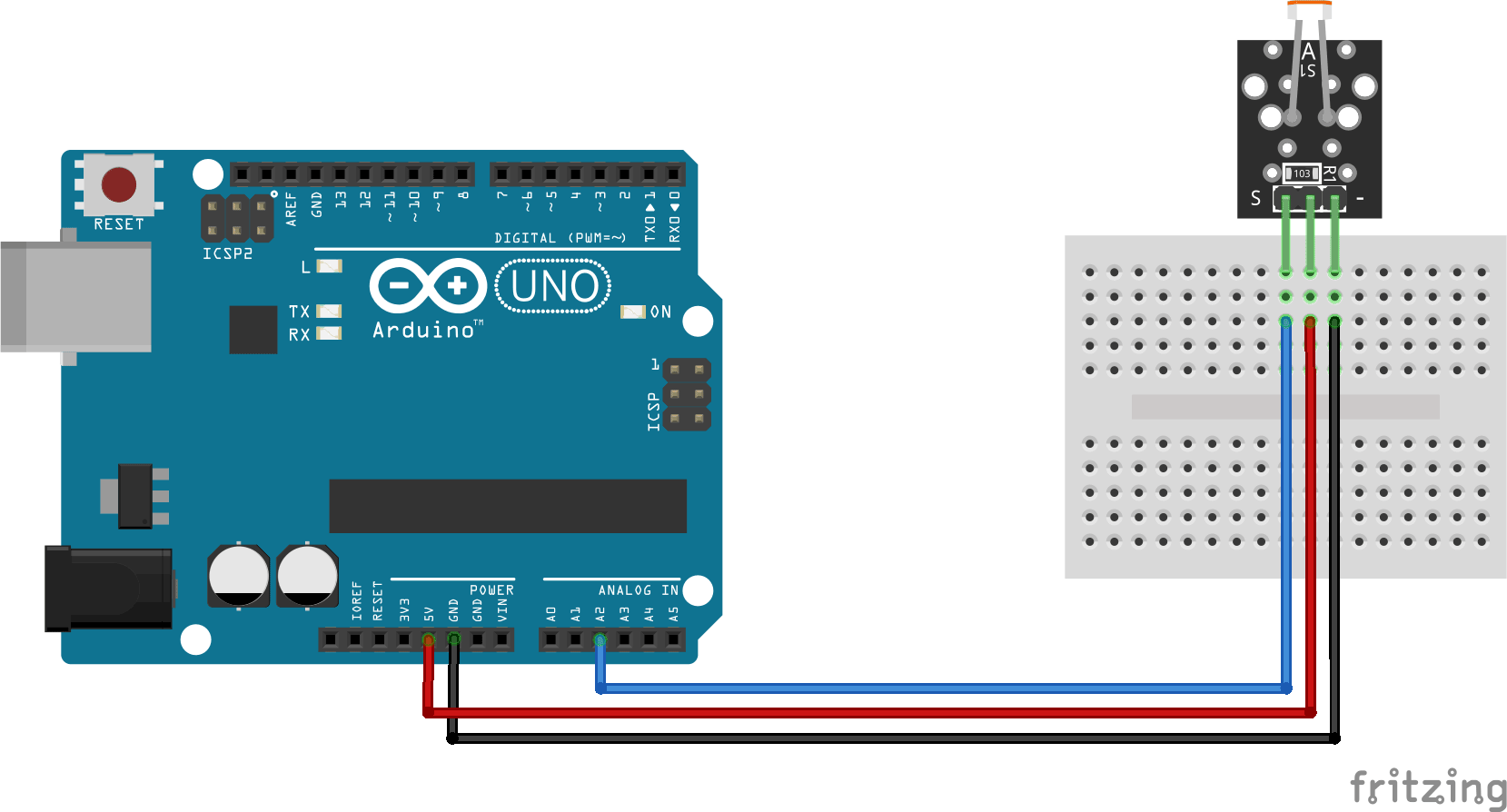

Wiring a sensor to an Arduino depends on the communication protocol in use. This tutorial will cover wiring with an analog sensor and a digital I2C sensor. All sensors mentioned in the tutorial are available at Treehacks. Many of them come with circuit boards that simplify the wiring.

We'll go over how to use one of Treehacks' photoresistors with an Arduino Uno. Take the sensor breakout and plug in one of the three pin attachment cables. This cable allows easy connection to an Arduino or breadboard. Plug the black lead (labeled GND) into a GND (ground, or 0V) pin on the Arduino, the red (labeled VCC) into the Uno's 5V pin, and the yellow/blue cable into A2.

Now that the sensor is wired, we've got to upload and run code to test it. Open (or download and open) the Arduino app, and open the file "photoresistor/photoresistor/ino" located in this repository.

/*

* Photoresistor sample code. Prints out value of photoresistor reading on analog pin A2.

*/

int pin = A2;

int val = 0;

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop() {

val = analogRead(pin);

Serial.println(val);

}This code is quite simple: it takes an integer analog reading and prints it to the Serial monitor, which can be opened from the Arduino app. You should see a stream of numbers:

283

290

294

305

309

315

318

330

349

354

356

363

368

370

The Arduino Uno's analog precision is 10 bits, or it provides analog readings from 0 to 1023. As a result, we can take each of these readings and divide them by 1024 to scale the brightness readings from 0 to 1. We could also scale from 0 to 5 volts by multiplying by 5V. From these raw readings, we can intuitively see relative brightness, or the difference between light and dark. With my finger over the sensor, readings rose to ~800; with my phone's light near it, they dropped to 30.

By consulting the datasheet for the photoresistor, we can then determine the ambient brightness in lux (a unit of illumination).

The heartbeat sensor is also an analog sensor. Connect its red lead to 5V, black lead to GND, and purple lead to A0. Then download and run this code. You'll see the LED on the Arduino Uno blink with your pulse!

Make sure static boolean serialVisual = true is true. Now, you should see this over serial monitor (baud rate 115200):

------------

------------

------------

--------------|-

--------------|-------

*** Heart-Beat Happened *** BPM: 63 --------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|-------------------

--------------|----------

--------------|---

--------------|-

--------------|-

I2C is a common communication protocol for sensors. We'll go over how to use the BMP180 with an Arduino. Take a four pin connection wire and plug it into the BMP 180's circuit board. Plug the red (VCC) wire into 5V, the black wire (GND) into GND, the white wire (SDA) into SDA on the Uno (may be labeled on reverse side) and the brown wire (SCL) into the Uno's SCL pin. The BMP 180 reads ambient pressure, which can be used to calculate an approximate altitude.

Unlike the analog sensor, the I2C sensor requires the Arduino to send it a message asking for the current pressure. Consequently, the process for reading data is more complex. Luckily, many mainstream I2C sensors have Arduino libraries that simplify this process. Download the Sparkfun BMP180 library from here, and put it in your Documents/Arduino/Libraries folder. You'll have to close and reopen the Arduino IDE every time you install a new library.

Navigate to File->Examples->Sparkfun BMP180->BMP180 Altitude Example, and download the program to your Arduino. When you open the serial monitor, you should see:

REBOOT

BMP180 init success

baseline pressure: 1002.33 mb

relative altitude: 0.3 meters, 1 feet

relative altitude: 0.4 meters, 1 feet

relative altitude: 0.6 meters, 2 feet

Note that the BMP 180 can also read temperature (not covered in this example code). If you see:

BMP180 init fail (disconnected?)

there is likely an issue with the sensor's wiring. Make sure that SDA on the sensor is connected to SDA on the Arduino, and SCL to SCL as well.

Let's take a quick look at how the code works. The Arduino sketch includes two external header files:

#include <SFE_BMP180.h>

#include <Wire.h>

One is the Sparkfun library - SFE_BMP180, and the other is Arduino's I2C communication library, Wire. The program creates an object, SFE_BMP180, that will be used to send messages through the library to the physical sensor. The setup() function initializes the sensor by attempting to send a message over I2C and receive an acknowledgement. If it fails, the program prints an error message and loops infinitely.

Otherwise, the loop() function runs. This calls getPressure(), which sends a request for the temperature (see explanation in code), reads the temperature, requests pressure, and then reads the current pressure, which is returned by the method and printed to the user.

Digital pins can also be used to output high (5V) or low (0V) voltage. Some digital pins are the Arduino are able to output voltages between 0V and 5V by quickly toggling the pin low and high; the corresponding output voltage is the percentage of time the pin is high multiplied by 5V.

Digital signals can be used to control lights, devices, or actuators. One simple example of using digital pins is controlling a small laser transmitter with an Arduino.

Often, the most efficient way to get started with other I2C or SPI sensors is to find an Arduino library and test out their example code. From that, it is generally fairly intuitive process to use a sensor in a more general application. For example, if you wanted to use the BMP 180 in an application that calculated pressure or altitude, it would be simple to use the double getPressure() method provided in the Sparkfun library in your code.

See our live site for sensors available during Treehacks.

This section of the hackpack covers the process of writing simple Arduino programs that interact with a computer. This permits fairly effortless interaction between sensors and desktop applications, such as visualizations of sensor data, peripheral control of computer systems, or controlling robotics devices.

We begin with a brief outline of serial communication and proceed to create a simple app that communicates from an Arduino to a desktop computer. Note that a similar procedure can be used to connect an Arduino to a Raspberry Pi.

Serial communication through a UART port enables an Arduino to send messages to other devices, such as a desktop computer or another Arduino. Serial communication is a frequently used protocol to send data among devices; prior to USB, many computer peripherals were serial devices. Today, UART ports are frequently used to send data from an embedded device, such as an Arduino or Raspberry Pi, to sensors, including a GPS or LCD display. For more information on the mechanics of serial communication, consult: https://learn.sparkfun.com/tutorials/serial-communication.

The serial monitor is perhaps the most important debugging tool for Arduino programs. See the "Hello, World" program as an example:

// The setup function is required and runs a single time when the program starts

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

}

// The loop function loops infinitely after the setup function returns

void loop() {

Serial.println("Hello, world!");

delay(1000); // Delay one second

}

To see "Hello, World" on your computer, open the Arduino application, choose the proper board (under tools -> board), and open the serial monitor. The example initializes serial communication with a speed of 9600 bits per second, so select 9600 after opening the serial monitor.

This guide does not cover using more complex sensors and devices with an Arduino, but a general outline of sending this data to a computer follows:

- Collect the data in some variable

- Print the variable to the Serial port

- Receive it with a desktop application

To start, install pySerial by running pip install pyserial in your terminal window.

Now, we will look at a basic program to read data from an Arduino:

import serial

ser = serial.Serial('/dev/tty.usbserial', 9600)

while True:

print ser.readline()

Save this in a file "serial_demo.py". This python program creates a serial port and prints any data received over serial. If you connect your Arduino and, from the directory containing "serial_demo.py" type "python serial_demo.py", you should see "Hello, World" printed on your computer. More complex applications and two way communication can be implemented using ser.write(val) to send messages back to the Arduino.

Processing can be downloaded at https://processing.org/. With similar syntax to Java, it is designed for building fairly simple graphical applications. Thus, making two or three dimensional visualizations of Arduino data is simple in Processing.

This guide will discuss a simple example in Processing for serial communication.

Serial myPort; // Create Serial object

String val; // For serial data

void setup() {

// Serial.list() provides a list (of strings) of all open serial ports.

// You may have to change the 0 below to 1 or 2 depending on the port your

// Arduino is using.

println(Serial.list());

String portName = Serial.list()[0]; // May change 0 to 1 or 2

myPort = new Serial(this, portName, 9600);

size(100, 100);

}

void draw() {

if ( myPort.available() > 0 ) { // If data is available in the serial port,

val = myPort.readStringUntil('\n'); // store it in val

}

if ( val == "Hello, world" ) {

background(random(255), random(255), random(255)); // change the background color

}

println(val); // print data to console

}Similar to Arduino, Processing sketches include a setup function, that runs once, and a draw function that runs repeatedly until the application quits. This program creates and opens a Serial port and prints any data received from the port to the console.

Though Processing and python provide some of the simplest methods for interfacing an Arduino with a computer, many other languages, including Matlab and Java, provide serial communication libraries for interacting with an Arduino.

It is possible to perform two way communication with the Arduino as well. Generally, it is good practice to perform some sort of handshake between the microcontroller and the computer to ensure both devices are sending messages when expected. This can be as simple as:

void testContact() {

// While there are no bytes incoming on the Serial

while (Serial.available() <= 0) {

Serial.println("ABC");

}

}Note that the line while (Serial.available() <= 0) will be true while there are no bytes waiting for the Arduino to process.

Official Arduino guide found here. Built-in tutorials found here.

MIT

HackPacks are built by the TreeHacks team to help hackers build great projects at our hackathon that happens every February at Stanford. We believe that everyone of every skill level can learn to make awesome things, and this is one way we help facilitate hacker culture. We open source our hackpacks (along with our internal tech) so everyone can learn from and use them! Feel free to use these at your own hackathons, workshops, and anything else that promotes building :)

If you're interested in attending TreeHacks, you can apply on our website during the application period.

You can follow us here on GitHub to see all the open source work we do (we love issues, contributions, and feedback of any kind!), and on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to see general updates from TreeHacks.