(image by Jo Wood)

The most enjoyable puzzles were days 3, 6, 7, 10 and 22. Day 25 was cute.

A recurring theme was an abstract machine, developed on days 2, 5, 7, 9 and then used to run inputs that served as block boxes on each odd-numbered day thereafter. (I didn't disassemble any of them.)

Another common AoC theme was path finding, seen on days 15, 18 and 20.

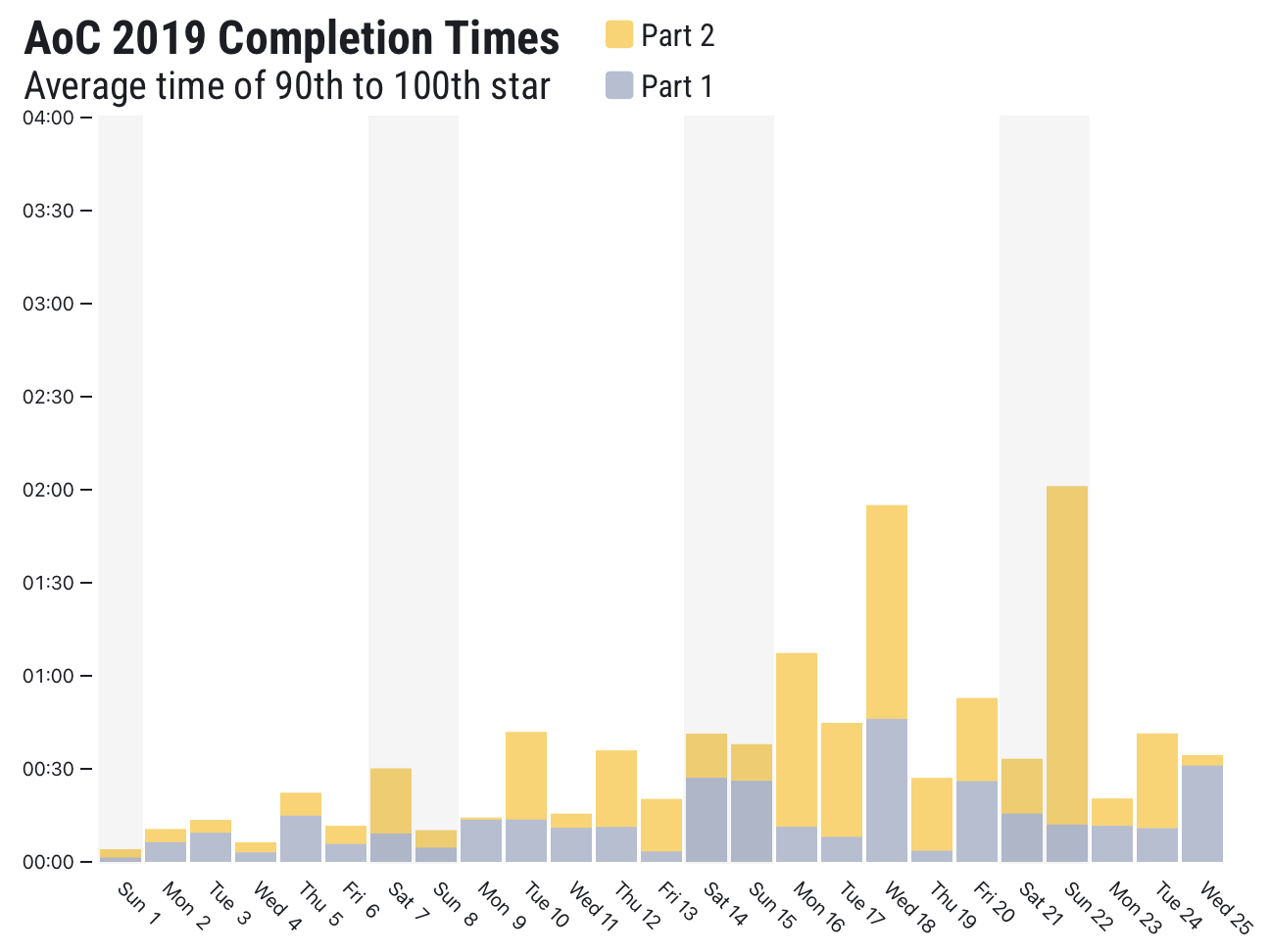

I have added difficulty ratings based on how long each puzzle took.

The puzzles started to get harder from day 13, but didn't have the sustained demands of the last half of 2018, and I managed to solve all of them without help. The major twist this year was the extensive use of the Intcode computer, which saved on parsing, but often limited our access to the real input.

Another simple one to start with. The first part is a trivial calculation, which is iterated in the second part.

Introducing this year's assembly language. The first part is straightforward implementation of the machine. The second part is an inversion, for which exhaustive search was sufficient.

On later examination, the code turns out to be relatively simple, not modifying any instructions that are executed later. The second and third instructions have no effect, but are there to provide a range of constants to be added or multiplied to the first input value, to which the second input value is then added, so it computes A*x + y + B for some constants A and B.

We are told the machine will be used later, with more instructions, presumably including one to set the instruction pointer from a value in memory. It is a stored-program computer that executes self-modifying programs with instructions of different lengths, so it's going to be tricky.

Generating the points visited by a wire is similar to previous puzzles. The rest was a nice exercise in operating on whole Sets and Maps.

(I initially solved a more general problem, having somehow missed that

there were only two wires. That was another nice exercise, using Map

and several applications of unionsWith.)

This is a smallish enumeration exercise. It can be handled with a generate-and-test approach, making one of the criteria the generator and the others independent tests. The non-decreasing criterion made an economical generator: even if you ignore the range and use all 10 digits, it still only makes 5005 lists. The second part involves replacing one of the tests. That would have been harder if it had originally been integrated with the generator.

It turns out even that was too much optimization. Simply using the range as the generator would be fast enough.

The task is to fill out the instruction set of the computer with I/O and addressing modes (part 1) and jumps and tests (part 2). It's all straightforward if tedious following of a detailed description. The computer now seems complete, presumably for more use later.

This was a nice little exercise involving a bottom-up view of trees. I used memoization for calculating the depth of each node in the first part because it's so easy in a lazy language, but a naive quadratic recursion would have been fast enough.

The second part can be cleanly decomposed into generating paths to the root and using those to count transfers. The paths require a similar accumulation to the first part, so I used the same structure again, even though we only need two of them.

This was fun. Using the Intcode program as a black box, the first part is a straightforward left fold over a list of instances with different phases.

The second part requires placing a slight modification of that fold inside a feedback loop, which is a big win for a lazy language. Then the Intcode computer needed to be updated to produce its outputs lazily.

There's a lot to read here, but after all that the problem is easy list

manipulation, using transpose twice in the second part.

The task is to add relative addressing to the Intcode computer and to explicitly remove a couple of restrictions that we may have imposed. This is fairly straightforward, and the supplied input program does some useful testing of the implementation. The resulting computer also solves part 2 with no extra work. We are told that the computer is now complete.

Now that the computer has relative addressing, it can express recursion.

For example, in part 2 the program implements f(A) + B for constants

A and B and the function f(n) = if n < 3 then n else f(n-1) + f(n-3)

(OEIS A097333).

This is an ingenious problem, requiring careful choice of representations and multi-stage use of sets and maps. The first part sets up the scenario, while the second takes it further.

In the second part, I constructed a representation of angles in discrete

2D space that gets them in the right order. atan2 on differences would

be prone to floating point precision problems, which could be fixed by

cancelling common factors first, but it seems more in the spirit of the

puzzle to keep everything discrete.

A moderate problem combining some previous themes: moving around on a 2D grid (day 3), running a black box Intcode program in a feedback loop (day 7), and displaying a bitmap image (day 8).

This is a clever little puzzle. The first part is a routine particle system (like day 20 of 2017 and day 10 of 2018). The problem statement for the second part suggests we need a more efficient simulation, but we only need to measure cycles (as in days 12 and 18 of 2018). This requires an insight into the structure of the system (and forgetting about real gravity).

I first did this using a repeating list abstraction from last year, but as pointed out in the reddit thread, there is a second insight which simplifies looking for a cycle.

Another question we could answer with a minor variation on this program is to compute the state of the system after N steps, for some very large N.

Day 13: Care Package ****

This was different. In past years, some of the least popular puzzles have been detailed simulations of intricate games (2015 day 22, 2018 days 15 and 24). This puzzle turns those around: we have a terse description of the game and an Intcode implementation, and we have to operate it. The first part is straightforward interpretation of the drawing instructions. The second requires a lot of exploration before it becomes clear what is needed. Prior familiarity with Breakout would have helped a lot here.

This was the first case that pushed against the limits of the lazy stream I/O in my Intcode implementation. The description suggests polling the state when the program wants input, and for the first input it's not clear when that is. Fortunately the game as given does not require the paddle to move at that point.

This was a novel and challenging puzzle. It took quite a while to work out how to make use of the leftovers, but in the end it comes out quite neatly when you traverse the DAG in topological order.

The second part is an inversion of the first, which is economically done with binary search.

This was a return of the path-finding theme from previous years, but in a tough problem: a droid bumping around a maze in the dark. I did the first part in two stages: map the maze and then search for a minimal path. Initially I was using an inefficient path finder, and the system ground to a halt as the maze grew. When I fixed that, it just worked. Since I now had an all-targets path finder, the second part was trivial.

I ended up using the path finder three times: to direct the droid to the closest unknown location, to find a path from the origin to the target once the maze was mapped, and to fill the maze in the second part.

On the Reddit thread, it seems many people got the first part more quickly using a depth-first search, but then had to implement a breadth-first search for the second part. While exploring the maze, I only thought of a sequential approach, but other people used multiple instances of the Intcode machine, restarting it from scratch for each branch or cloning it at each branch point.

This puzzle doesn't require much code: the challenge is finding a useful pattern in the process.

The first part is a fiddly calculation, but not too complicated, while the second is described as applying the same process to an infeasibly large input. Finding a faster way involves getting some insight into enough of the behaviour of the process to provide the answer for inputs with a certain property, which the given input has.

The first part focusses our attention on the front of the list, but the behaviour at the back is what matters for the second part (for the given input), and that turns out to be much simpler than at the front. There's even a formula for n phases involving binomial coefficients, and it might be possible to exploit the repetition in the input and the modulo 10 calculation, but a naive implementation is fast enough.

This was challenging enough, but the description made it look a lot harder. We are told that the "scaffold" is in fact a single path the loops back across itself. The easy first part directs our attention to the crossings, but these should be ignored in the second part, where we just follow the path.

The second part is a search for a compact encoding of the path. The constraints we are given are quite tight, so the search is narrow.

Another maze solver, with the complication of keys and doors. The second part talks about parallelism, but is actually about interleaving moves. (A version with the robots moving in parallel would also be interesting.) It becomes vital to control the number of states, which can be done by using two levels of path finding.

It seems that in all of the supplied inputs the maze is a tree, which simplifies things a bit.

This was a novel idea. The first part was straightforward. The second requires us to map out the beam and perform a calculation on that map. In the examples, the horizontal width of the beam is monotonic nondecreasing, but that doesn't hold for the input. The main challenge is then not getting all these numbers mixed up and avoiding off-by-one errors.

Two novel twists on maze solving. Parsing the input was quite tedious, especially locating the 2-letter portals. After that, each part was a neat breadth-first search with a little setup.

This was quite complicated, but ultimately unsatisfactory. We have to construct a propositional formula for when the droid should jump, translate it into a restricted instruction set, and test that on an Intcode computer. It takes a bit of experimentation to understand what is going on. After all that there seems to be a clear best formula for the first part.

For the second part, with more lookahead, it's harder to work out clear criteria for comparing formulas. One of my experiments succeeded, but so does a more elaborate formula, and it's not clear whether they both handle all possible situations.

From the discussion on Reddit, it emerges that simpler solutions to the

first part are accepted, because the input program doesn't use tests like

##.##.#.#. I wonder whether the second part has similar issues.

Day 22: Slam Shuffle ****

This was a fun challenge, with some similarities to day 16 of 2017. The setup is described in terms of lists, and such a representation is adequate of the first part, but is already a bit slow, and will clearly not be adequate, when (as expected) things get much bigger (in two directions) in the second part.

The huge number of steps suggests that we'll be defining a semigroup of permutations so that we can use the log-time repetition algorithm. The huge size of a permutation suggests we need a compact representation for a subset of permutations including the primitive shuffles and closed under composition. Getting this right is tricky, and I went through a series of representations, convincing myself that each was equivalent to the one before.

The final question asks us to go in the reverse direction, so we need to be able to invert our permutations, for which we need to brush up on a bit of modular arithmetic.

Setting up a network of Intcode computers. Both parts are just following the instructions, with no particular challenge.

Another cellular automaton: routine in part one, but with an interesting twist in part two. In the first part, I took the hint from the rating function to use a bitwise representation of grids, but that probably wasn't necessary. In the second, I had a correct implementation but didn't realize it for quite a while because the example omits empty grids at both ends.

In a cute twist, we are given an Intcode computer running a simple relative of the Colossal Cave Adventure (aka ADVENT). The simplest approach is to explore the game by hand and write an exhaustive search for the blind knapsack problem at the end. The shape of the maze and the names of the portable items vary between different users' inputs, though.